Bezos Earth Fund gift of $100 million to The Nature Conservancy for nature-based climate solutions includes $20 million to support Indigenous-led conservation and carbon sequestration through our Emerald Edge program. The rainforests of the Emerald Edge harbor globally significant biodiversity and carbon stores. The average annual rainfall of more than 115 inches results in large, long-lived trees which are not affected by the pests and fires of many forests in Western North American.

Olympic Rainforest—Climate Resilience for forests, salmon and people

Beyond 60: Indigenous Knowledge Strengthens Conservation & Community

Returning to the territories of his First Nation, the Ahousaht people of Clayoquot Sound in British Columbia, the first thing Tyson Atleo always hears is, “Welcome home, it’s nice to see you here.”

That sense of being truly home deepens when Atleo, the son of an Ahousaht hereditary chief, paddles up the blue-green rivers where salmon spawn, steelhead laze in cold, deep pools and eagles rest in the branches above. Those watersheds “are like the arteries of this place,” he said, “that’s where we get our life from.”

Out on the beaches, you might see wolf tracks in the sand or spot a grey whale in the surf. “You get this westerly breeze in your face, fresh sea air, then turn around and cross this threshold into Sitka spruce and old-growth forest,” Atleo said. “And whoosh, you're bombarded with green and this infinite stimulus, it's infinitely complex.”

Clayoquot Sound sustains the last old-growth forests on Vancouver Island and is a critical piece of the largest intact coastal rainforest on Earth known as the Emerald Edge. Spanning 100 million acres across Alaska, British Columbia and Washington, the Emerald Edge supports as much biodiversity as its tropical counterparts and more than 50 Indigenous peoples and myriad communities.

“Our people and our culture are being grown by the lifeblood of this place, and being informed and shaped by it,” Atleo said. “So it’s more than a home. It’s a caregiver, it’s a teacher.”

Community-Centered Conservation

How can The Nature Conservancy work at the scale of the massive Emerald Edge ecosystem? That’s the question we asked ourselves about a decade ago. The answer, says Emerald Edge Director Eric Delvin, rested with the local and Indigenous peoples whose lives are intertwined with these lands and waters.

“The most effective approach is to invest in the people who have lived there since time immemorial and know how to take care of it,” Delvin said. “The research, as well as our own experience, tell us this works.”

That experience includes nearly 15 years supporting the development of the Great Bear Rainforest agreement in the heart of the Emerald Edge. First signed in 2008 and finalized in 2016, the historic agreement among 27 First Nations and the British Columbia and Federal governments protects 9 million acres of forest from logging and requires sustainable practices on millions more. The Conservancy raised $39 million towards a $120-million endowment to support the capacity of these nations to manage their lands and build sustainable economic opportunities.

Today in the Great Bear Rainforest, member nations are stopping pipelines from crossing their territory and enforcing new regulations — prompted by indigenous knowledge — prohibiting grizzly bear trophy hunting. First Nation communities have created 45 new businesses and 767 new permanent jobs.

“What we see,” Delvin said, “is that if you make sure communities that really care about a place have livelihoods and management authority, you’re going to have really good conservation outcomes.”

Also read: Beyond 60: The Nexus of People & Nature in the Central Cascades

Matching Conservation with Tribal Priorities

The success of the Great Bear Rainforest agreement prompted other First Nations in the Emerald Edge to reach out to the Conservancy.

“Because of the leadership the Conservancy had shown in the Great Bear Rainforest agreements,” Atleo said, the hereditary chiefs invited us into his community about a decade ago.

“Our leaders in Clayoquot Sound recognized that those agreements allowed the nations in the central coast to conserve and protect some of their land base... while also generating economic value from that conservation work,” said Atleo, who helped lead the development of his nation’s vision for their territory. He has since become the Economic Development Lead for our Emerald Edge and Canada programs.

Early in the partnership, the Conservancy provided small capacity grants to help the Ahousaht stand up a stewardship office and support community conversations around people’s values for the land and how those could be supported.

“We knew we would not be successful if we went in and said, ‘We want to protect this for you,’” Delvin said. “We needed to go in when we were invited in and really support the capacity of each nation to envision a different future.”

At one meeting, an Ahousaht chief rolled out an old map covered with hundreds of dots marking important points in their territory, Delvin recalls. The Conservancy pulled that information into a digital map with all of the place names in the Ahousaht language, which the nation then shared in meetings with the provincial government.

“Through that process, the Ahousaht were able to more effectively communicate to the Provincial government where culturally important places were,” Delvin said.

As a result, the final maps captured places that were culturally valuable, as well as those scientists had identified as ecologically important. “So they were fully endorsed by the community,” Delvin said.

In addition to the Ahousaht, the Conservancy worked with the Tla-o-qui-aht and Hesquiaht First Nations, whose territories also lie in Clayoquot Sound. The three nations are now negotiating with the British Columbia government to implement their conservation visions, which include permanent protection for about 300,000 acres of forest. The Conservancy is helping ensure the nations have the expertise and capacity to engage effectively in those talks.

Just as important, says Atleo, the nations’ land use visions ensure that they benefit from the area’s natural resources. Clayoquot Sound’s growing tourism economy has left out First Nations, with on-reserve household income roughly half that of other communities in the area. “We can’t expect people to want to conserve while staying in poverty,” Atleo said.

To that end, the Conservancy is raising $16.5 million toward an endowment to support sustainable stewardship funding in Clayoquot Sound, such as hiring natural resource managers, reconnecting youth to their territories and fostering sustainable businesses.

In the Great Bear, investments made possible by that earlier endowment are coming to fruition. “For kids now in college or coming back from college,” Delvin said, “there's a place for them and an economy built around stewardship, fisheries and tourism, and this healthy dependence on the natural resources.”

The Great Bear endowment is also providing communities in that region with “a bit of a buffer” during the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic, Delvin pointed out. Once in place, the Clayoquot agreements and endowment will help those communities be more economically resilient too.

We’re also ensuring that Indigenous peoples across the Emerald Edge — and beyond — have opportunities to learn from each other.

After conversations with their counterparts in British Columbia, Native Alaskan leaders decided to start their own stewardship endowment and have pledged $10 million. Meanwhile, leaders from Emerald Edge communities traveled to Australia to meet with indigenous peoples there, and they came away with a social media strategy that contributed to British Columbia’s trophy hunting ban.

“The greatest thing we’ve learned in the Emerald Edge program is the power of bringing people together,” Atleo said. “Providing a safe space for people to express themselves, build trust, feel connected to their peers — this is where real learning happens, and where we can see some significant, scaled impact.”

Trust as an Essential Element

Through its work in the Emerald Edge, the Conservancy has learned a great deal about how to build good working relationships with indigenous communities. But it’s not always easy, both Atleo and Delvin acknowledge.

“It's very hard for people to imagine a reality that is different from what has been offered for the last half a century, which is, ‘We will take from you and not give anything back — we will take the timber, we'll take the fish,’” Atleo said. “So words like ‘protection’ are scary to those communities.”

We can’t forget that past, Atleo emphasized. “Sixty years ago, the intent was to oppress that [indigenous] way of thinking of being on the planet,” he said. “Yet here we are in 2020 celebrating the potential for indigenous cultures to inform the rest of the world how to care for natural systems.

“And that’s why building trustful relationships in indigenous communities is so important,” he said. “Washington is a leader in showing how to do that across the Conservancy.”

In Washington and across North America, our evolving partnerships with indigenous communities have spurred us to think differently about all of the lands we own and manage, says Director of Conservation James Schroeder.

Places that we protected a few decades ago for their habitat value or unique geology have been important to tribes forever. Ancestral lands and waters were integrally represented and reflected in systems of governance, society and spirituality; yet tribes in many cases were forced to give them up. These spaces have provided not only food and sustenance for generations, but also community and identity.

Today, Schroeder said, the Conservancy is taking a closer look at how protecting ecological values can also protect cultural and social values. We’re also exploring opportunities to return ownership and management of lands we hold to tribes.

“How do we support tribes to exercise their treaty rights and have access to the resources they've been promised?” Schroeder said. “Because many of those resources can come from properties that we manage and steward.”

“We can’t achieve our long-term conservation goals of healthy lands and waters and a livable climate without the support and knowledge of indigenous communities.”

Rural Leaders Ensure Nature & Communities Thrive

Milestone for First Nations-led conservation in Clayoquot Sound

The federal government of Canada has committed to funding the land-use visions and authority of First Nations for the iconic Clayoquot Sound as part of a groundbreaking announcement earlier this week. It will help to establish major new protected forest and coastal areas as well as provide funding to support them.

Milestone for First Nations-led conservation in Clayoquot Sound (Copy)

The federal government of Canada has committed to funding the land-use visions and authority of First Nations for the iconic Clayoquot Sound as part of a groundbreaking announcement earlier this week. It will help to establish major new protected forest and coastal areas as well as provide funding to support them.

Fisheries Market Analysis - Request for Proposals

Frank Conversations at Neah Bay About Indigenous Leadership

Indigenous People at the Heart of Conservation

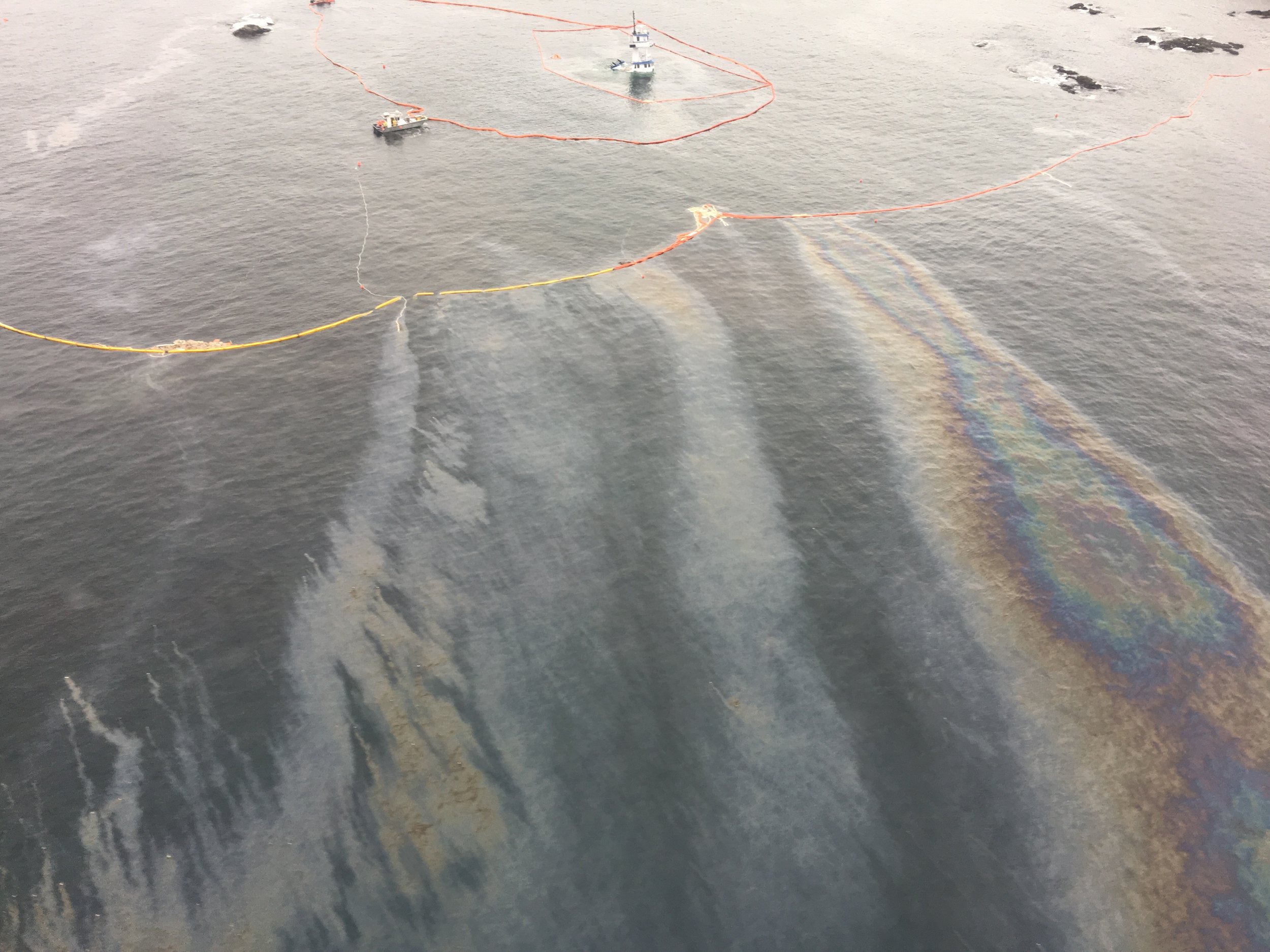

Keeping Danger at Bay near the shores of Bella Bella

Photographed by Heiltsuk Nation

It has been 12 days since a Texas-owned tug boat and its empty fuel barge crashed on rocks near Bella Bella, a First Nations community in the Great Bear Rainforest, leaking thousands of liters of diesel fuel. "It's an environmental disaster. It's a cultural disaster. It's affecting every facet of our community," Jess Housty of the Heiltsuk First Nation told one Canadian media outlet just days after the spill. Housty is also a Board director for TNC Canada, building on a 10-year partnership between TNC and the Heiltsuk Nation. Here at the Conservancy’s Washington chapter, we are deeply saddened by the spill and stand behind the Heiltsuk, who are working from dawn to dusk to mitigate the environmental and cultural damage.

The Great Bear Rainforest is at the heart of what the Conservancy calls the “Emerald Edge”—100 million acres of the largest remaining coastal rainforest on Earth, stretching from Alaska’s Tongass Forest to Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Great Bear’s old-growth forests, rivers and coastal waters are the homeland of many First Nations, as well as extraordinarily rich habitat for grizzlies, wolves, several species of salmon, whales, eagles and other wildlife. It is the only home of the Spirit Bear, a rare subspecies of black bear that has white fur.

Clam beds are slicked with fuel, and just yesterday, divers confirmed that endangered abalone had been poisoned, as well as kelp and juvenile herring—all connected to Heiltsuk sustenance and livelihoods. Orcas and other sea life has been spotted traveling through the contaminated waters. Governmental response to the spill has been inadequate, and the sunken tug has not yet been recovered.

The Heiltsuk have started a fundraiser to cover their spill recovery costs and a community investigation into the accident and its impacts. To monitor the recovery efforts, check out the Heiltsuk Tribal Council Facebook page.

Learn more about our work in the Emerald Edge

The Many Gifts of Herring in the Emerald Edge

Nature signals spring. In Texas it is blue bonnets, in New England, robins, and for the Emerald Edge of Alaska, British Columbia and Washington, it is the return of herring.

Written & Photographed by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

For millennia, Pacific herring have been harbingers of spring. Historically, they returned in great numbers to spawn on kelp, seagrass and gravel throughout the Pacific Northwest. Their arrival was quickly followed by horde of sea lions, humpback whales, seabirds, and eagles all gorging on this plentiful prey. And in their wake, killer whales arrived to eat the sea lions and whales. With the arrival of herring, the waters of the Emerald Edge erupt with life.

And for the indigenous people of the Emerald Edge, herring eggs bring the first pulse of fresh food of the season. For the Haida, Tlingit and many other peoples, herring eggs are perhaps second only to salmon as the most culturally revered food. The Haida gather herring roe on kelp, while Tlingit set hemlock branches in the water and collect the thick layers of herring eggs that coat the limbs. Those who gather the delicacy will eat it themselves, share with family and friends locally and in distant communities, or trade for other products. Every feast and celebration will be accompanied by mounds of bright herring eggs that connect people to each other, their past and to the ocean.

Herring also signal the opening of the fishing season for commercial fishers. Many fishers who latter will focus on the lucrative salmon fishery, start their year with herring. In Southeast Alaska, over the last decade these boats scooped up an average of about 13,000 tons, annually. The unspawned roe is coveted in Japan, and in recent decades this has become a lucrative market. Both the income generated by the herring and the opportunity to break in new crew at the beginning of the season are critically important for many fisherman.

Herring are thus central for nature, for culture and for the economy of coastal communities. However, historic overfishing, pollution, coastal development and climate variability have resulted in many declining stocks of herring. In some places, the number of fish is so low that fisheries have been closed for years. In recent times, then, herring has not only announced spring, but has also marked a time of conflict.

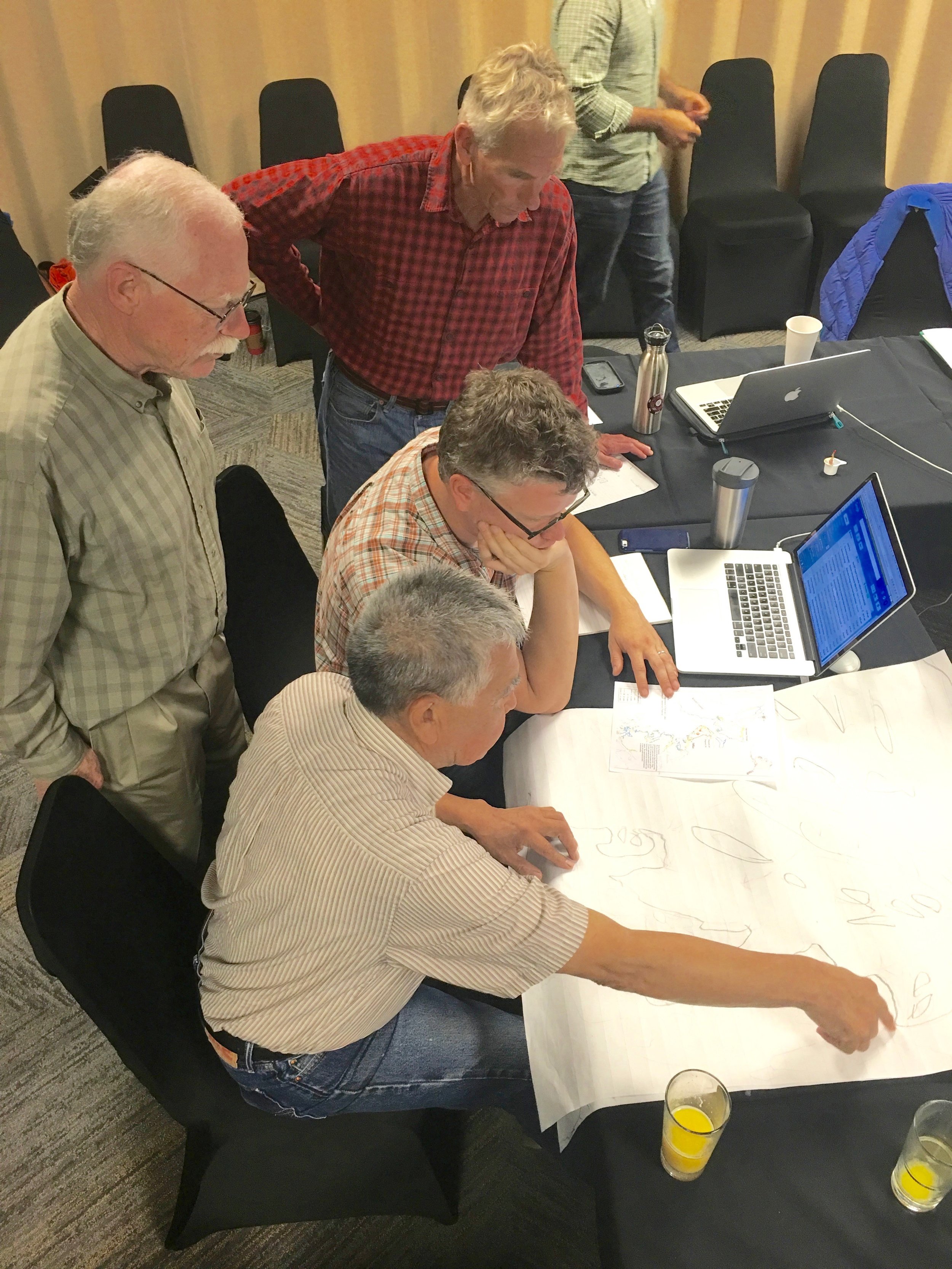

Last year, my colleagues from the Ocean Modeling Forum (OMF) and I brought together more than 125 First Nation and Tribal Elders, governmental officials, scientists and environmental NGOs and asked what were the critical science gaps for science management. As one of the directors of the OMF, my role is to connect diverse types of knowledge and bring it to bear on pressing ocean management issues. In the case of herring, we learned that the extensive traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often marginalized in management, and the cultural costs and benefits of herring are not adequately considered in decision making.

To fill these gaps the OMF created a working group of 18 social and natural scientists, traditional knowledge holders, commercial fishers, and resource managers to tackle this problem. I just returned from co-chairing the 3rd meeting of the OMF herring group (with Dr. Tessa Francis from the University of Washington Puget Sound Institute) which met in Sitka, Alaska. The group has made great strides in incorporating traditional knowledge into quantitative ecological models – the language of fisheries management. Working collaboratively across our professional silos, we have developed the means to formally examine management alternatives to determine their ecological, economic and cultural outcomes—the triple bottom line.

After the OMF meeting concluded, I had the privilege of visiting historic and current herring spawning grounds with Harvey Kitka – an elder of the Sitka tribe. Each cove and beach seemed to have a story of plenitude and demise. Harvey spoke about the time when herring were so abundant that they jumped from the water and the crack of their bodies hitting the ocean’s surface would echo across the Sound like hail. Those days are gone. Instead, Harvey pointed to islands were there was just a little spawning here and a little spot there. He spoke with sadness about the present, but was always optimistic about the future, and the work we are trying to do.

Solving difficult conservation problems, like herring conflicts along the Emerald Edge, will require new approaches and innovative thinking. My experiences working with a diverse group of people with vastly different perspectives on herring, suggest that given the chance people can rise to the occasion and tame these wicked problems.

Learn more about our work in the Emerald Edge

Camping in Paradise

Written & Photographed by Carrie Krueger, Director of Marketing, The Nature Conservancy in Washington

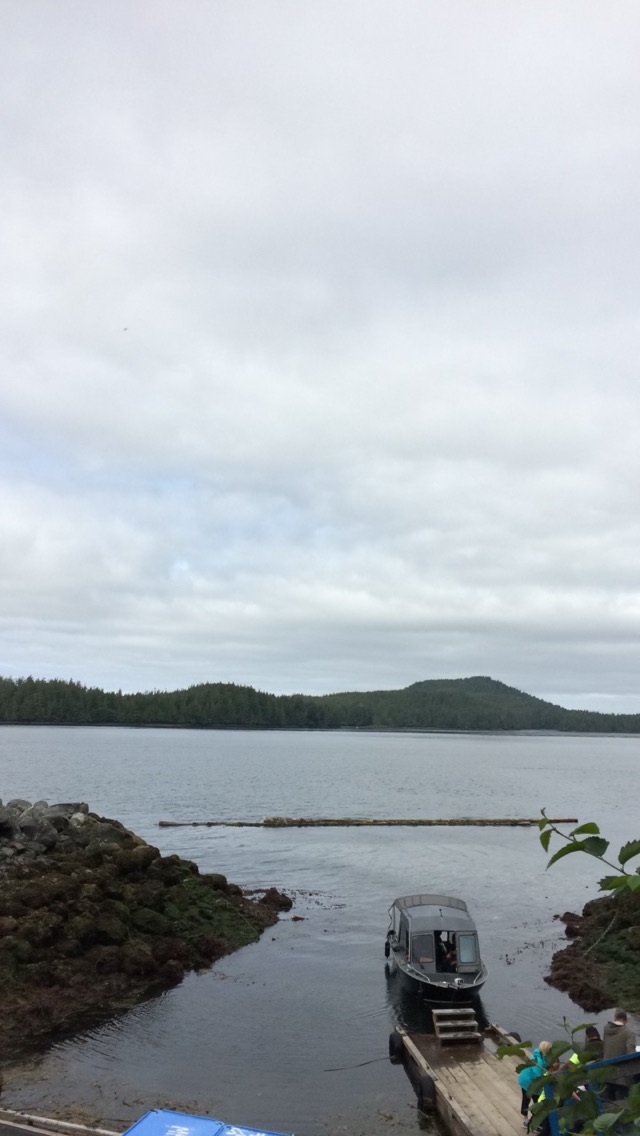

Clayoquot Sound, on Canada’s Vancouver Island is a spectacular place of sea and forests, centuries of culture, and home to First Nations with deep connections to the land and water. As the region’s indigenous people look for ways to protect cherished natural resources they are also sharing the area’s abundance with others. One example: The Lone Cone – a campground and hostel located in the heart of this rich ecological treasure and open to all to enjoy.

A short boat trip takes visitors to the Lone Cone, for camping, dormitory style housing or even private rooms along with a community kitchen, game room and hot tub. But it’s the access to nature that attracts visitors – from tents with a view to hiking trails and beaches, nature abounds. Kayaks, paddleboards and mountain bikes are available as part of the eco-tourism experience.

The Lone Cone is an example of community based conservation that protects nature while creating local economic opportunities. The site has created more than 20 jobs and attracts visitors from around the world. It is run by the Ahousaht First Nation which has plans for other sites and attractions in the area.

It’s a tiny piece of the vast Emerald Edge, a Nature Conservancy priority that spans from Washington, through British Columbia and all the way to Alaska. The landscape holds the largest intact coastal rainforest and is of massive ecological importance to the world. Through our work we are committed to partnership with indigenous and local people to heal the lands and waters while creating new opportunities for local wealth creation, economic development and entrepreneurship.

LEARN MORE ABOUT LONE CONE

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK PROTECTING THE EMERALD EDGE

Quinault Indian Nation named Title Sponsor for Washington Coast Works Sustainable Business Plan Competition

June 21, 2016 (Seattle, Washington) — Washington Coast Works is pleased to announce the Quinault Indian Nation as the Title Sponsor for the 2016 Sustainable Small Business Competition. This year’s business training is underway and will conclude July 22-24 during the Entrepreneurship Summit at the Olympic Natural Resource Center in Forks, Washington. At the Summit, participants will develop their presentation pitch and polish their business plans for a chance to vie for up to $20,000 in startup financing. Winners will be announced in October.

This year’s participating entrepreneurs include a cultural tourism business, a wood boat kit manufacturer, a bee keeper, a construction business, a chocolatier, a tiny homes builder, a food truck, a dog boarding business, a permaculture farm, a stump grinder, a nature-inspired fitness company, a sustainable vegetable and hog producer, and a manufacturer of art equipment. All are “triple-bottom-line” businesses from coastal communities in Grays Harbor, Jefferson and Clallam Counties and designed to generate profits with significant social and environmental benefits.

“The Quinault Indian Nation is a critical partner for us,” said Eric Delvin, Emerald Edge Project Manager at The Nature Conservancy. “Their commitment to conservation of their natural resources and to sustainable economic development is clearly demonstrated by their sponsorship of Washington Coast Works.”

Other 2016 competition sponsors include Enterprise for Equity and Washington Department of Commerce.

Washington Coast Works is an initiative of The Nature Conservancy in collaboration with Enterprise for Equity (with support from a USDA Rural Business Development Grant), the Center for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, and the Ta’ala Fund, a native community development financial institution that supports business development in western Washington coast tribal communities.

The complete calendar of events leading up to the competition is available at www.wacoastworks.org. Contact at Mike Skinner info@wacoastworks.org to learn more about the competition, to volunteer to mentor or judge, or to request information about more sponsorship opportunities.

Sustainable Small Businesses Move Forward with Washington Coast Works

MAY 31 (Seattle, Washington) — Fifteen emerging entrepreneurs from coastal communities in Grays Harbor, Jefferson and Clallam Counties are participating in an intensive 8-week business development training provided by Enterprise for Equity as part of the 2016 Washington Coast Works Sustainable Small Business Competition.

Participating businesses include a permaculture farm, a wood boat kit manufacturer, a construction business, a chocolatier, a bee keeper, a tiny homes builder, a dog boarding business, a cultural tourism business, a nature-inspired fitness company, a stump grinder, a sustainable vegetable and hog producer, a manufacturer of art equipment and a food truck — all “triple-bottom-line” businesses designed to generate profits with significant social and environmental benefits.

The training concludes in late July with an Entrepreneurship Summit to be held at the Olympic Natural Resource Center in Forks, Washington. At the Summit, participants will connect to a team of volunteer mentors and advisors who will help them develop their pitch and polish their business plans for presentation to a panel of judges in mid-September, and for a chance to win up to $20,000 in startup financing. Winners will be announced in October.

“It (the competition) gave me a new lease on life — something that I want to do for my community. I want to build our community”, said Jean Ramos, a winner from last year’s competition working to launch a sustainably foraged Labrador tea business.

Liz Ellis, another winner in last year’s competition, used her award to launch East Aberdeen Community Farm.

“I feel so fortunate to have been part of the three days of very intensive workshops,” Ellis said about last year’s Summit. “For me, the most valuable part of the competition was learning and being inspired by professionals and people in business, coaches and economists, and the fellow applicants from the north and the south.”

Washington Coast Works is an initiative of The Nature Conservancy in collaboration with Enterprise for Equity (with support from a USDA Rural Business Development Grant), the Center for Inclusive Entrepreneurship and the Ta’ala Fund. The program is designed to diversify the economies in Grays Harbor, Jefferson and Clallam Counties and contribute to a new vision of sustainable community and economic development on the Washington Coast.

The complete calendar of events leading up to the competition is available at www.wacoastworks.org. Contact Enterprise for Equity at (360) 704-3375 ext. 3 or Mike Skinner info@wacoastworks.org for more information about the competition.

Story Contacts

Robin Ohlgren

WA Coast Works Fundraiser

P | 208-301-1011

E | robin@ohlgren.com

Liz Ellis

East Aberdeen Community Farm

P | 360-780-0349

E | harborsolar@yahoo.com

Jean Ramos

SovereigNDNTea

P | 360-780-0349

E| jeanniebug.123@gmail.com

Great Step Forward for Great Bear

The Great Bear Rainforest is a land of towering trees, salmon-filled rivers and peoples with a presence as old as time. On Feb. 1, we celebrated as the government of British Columbia and the governments of 26 First Nations signed an historic agreement that will forever conserve 19 million acres in British Columbia, banning logging on much of the land and setting stringent ecological protections on the remaining portions.

Getting to this agreement is a triumph for many – including indigenous people, conservationists, the forest industry, the provincial government and The Nature Conservancy.

Exploring an Emerald Edge: February Photo of the Month

Written by Tom Parker, Northwest Photographer

Little Qualicum Falls is one of my favourite stops when I'm headed north on Vancouver Island. Located near the centre of the island it has a great mix of lush forest greens and sparkling waterfall blues packed into a beautiful 1km loop. With the river always fluctuating throughout the seasons the landscape is constantly changing, creating new scenes each time I visit. In the winter months the river has so much power that it is constantly shifting massive fallen trees down the banks, sometimes creating natural bridges or leaving them in precarious spots for viewing such as hanging from the tops of waterfalls.

On this day my friend Forest was in town and wanted to see the island, so we headed down the Alberni Highway looking for adventure with our first stop at the falls. When I was shooting the river Forest had disappeared and the next thing I knew he was climbing across the logs making his way over the river. Its always inspiring to go exploring with friends that are not afraid to leave their comfort zone. As a photographer I’m always looking to push new boundaries, personally and with my work.

Nature inspires my photography in many ways, from the slowing of time to the roar of the rivers washing away distractions, allowing my creativity to flow. When I am out in the woods it is as if time stands still, very little seems to affect me; the cold, the wet or the feeling of hunger drift to the back of my mind and all I focus on is the present. With the weather always changing on the island my favourite hikes rarely look the same, always providing a fresh perspective. It also means that to catch these sudden changes in weather I try to be outside as much as possible. The light and fog may only be around for a few fleeting moments but sometimes thats all you need.

Born and raised on Vancouver Island, Tom has spent most of his life exploring the outdoors. His work is inspired and influenced by the beauty that unfolds before him in nature. Follow him on Instagram: @tomparkr. Visit his website: tomparkerphoto.com

Partners, Transformation, Salmon

Connecting with the community on the Olympic Peninsula

Written and Photographed By Byron Bishop, Board of Trustees Chair, The Nature Conservancy in Washington

There is no substitute for hands-on experience. As the incoming board chair for The Nature Conservancy in Washington I hear an awful lot and talk an awful lot about the environmental challenges our state is facing and the ways in which this organization is tackling them. But a recent trip to the Olympic Peninsula gave me an up-close view of the issues, allowed me to meet vital partners and inspired me to work even harder to build success for people and nature in this critical region.

I was privileged to spend time with leadership from both the Makah Tribe and the Quinault Indian Nation. Each of them is uniquely connected to the lands and waters of the region, and each plays a big role in assuring the health of forests, rivers, coast, and ocean. We greatly value our partnerships with the Makah and Quinault, which are built on shared values and goals. For example, one area of mutual concern is the threat of an oil spill. I toured the only oil skimmer at Neah Bay and learned that there is no capability for handling a large spill. Together we are working to diminish the risk of spills and increase our ability to respond, preventing environmental devastation. After productive meetings with each tribe, we look forward to deeper partnerships.

The region is part of a larger system along the Emerald Edge from Washington through British Columbia and up to Alaska. On this trip I learned more about the strategy of transforming forest practices across this region. In each area there is a different primary tactic: In Washington we will use changing ownership structures. In British Columbia, it is about changing how tenure works and empowering First Nations. In Alaska, we must transition industry from old growth to second growth. With a high level vision of transformation, we have the versatility to create the most powerful solutions for each area.

No trip to the region is complete without talking salmon. The iconic fish thrives where there are healthy forests and rivers, so their well-being is a very good indicator of how the system is doing. I witnessed several positive signs: Along Hurst Creek, a tributary of the Clearwater on Conservancy property, I saw engineered log jams that will be added to the creek to create spawning habitat. Along the Clearwater, a recent Conservancy acquisition, I saw property that has great potential to become prime spawning habitat, with your support. Our work to increase salmon productivity in places where salmon once flourished is an important piece of a much larger plan, and satisfying to witness first-hand.

Every trip on behalf of The Nature Conservancy leaves me inspired, and convinced we are making a large and positive impact on our state. This trip reminded me of the complexity of dealing with multi-faceted issues in a wild and treasured place.

Hoh River Protection

More than 3,000 acres will increase the protected area along the Hoh River

Written by Megan Sheehan, Senior Editorial Manager, Digital

Photography by Bridget Besaw

They say fish have short memories, but the salmon in Washington State will remember the newly protected 3,000+ acres in Washington State for a long time. 3,184 acres along the Hoh River – extending from Olympic National Park to the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary – are now protected for people and nature.

This new protected area creates a 32-mile corridor of critical and protected habitat for a variety of species, especially the trees and salmon, which in Washington grow faster than anywhere else in the world. This work builds on what the Hoh River Trust has been doing to ensure these lands, waters and creatures can thrive and grow for future generations.

All the Conservancy’s land on the Washington Coast continues to be open to public and tribal use for hunting, fishing, traditional gathering of plants and medicines, boating, birding, hiking, and other coastal outdoor activities.

Saves like this bring us hope for the future, and show that when we all work together, we can accomplish things greater than ourselves. Read more details about the Hoh River acquisition.

NATURE CONSERVANCY RAISES $33.3 MILLION FOR CONSERVATION

Private donations transform work to restore natural systems in Washington and around the world

SEATTLE: The Nature Conservancy’s three-year Forces of Nature campaign has raised $33.3 million in private dollars for conservation in Washington and internationally. The campaign, the largest in the chapter’s history and one of the largest campaigns for conservation ever in Washington, was focused on conserving and restoring natural systems while enhancing the well-being of people.

“Our economy and quality of life are intertwined with our state’s clean water, abundant natural resources and astounding beauty,” said Mike Stevens, the Conservancy’s Washington director. “Through their generosity to this campaign, the people of Washington have shown they understand and value what we have and are willing to work to steward it.”

“We are grateful to our donors who have demonstrated their passion and commitment to conservation even during difficult economic times,” said Campaign Chair Elaine French, a volunteer and member of the state chapter’s board of trustees.

In all, the Conservancy raised nearly $18 million for acquisitions, $10 million for on-the-ground work, and more than $6 million for international programs.

Funds raised through the Forces of Nature Campaign are already bringing results.

- Puget Sound: Partnership-driven, high-impact projects are blending flood protection, salmon habitat, stormwater reduction and agricultural preservation across more than 1,000 acres of floodplains along eight major rivers.

- East Cascade Forests: Critical timberlands have been brought into public ownership and we are partnering to restore forests to reduce the risks of catastrophic megafires, while promoting ways to ensure the economic viability of forest-dependent communities.

- Olympic Rainforest: We are working hand in hand with coastal communities to conserve and restore forests along our most important coast salmon rivers.

- Marine Waters: A new program focuses on conserving Washington’s 28,000 square miles of marine waters and fisheries in Puget Sound and off the coast.

- Emerald Edge: A new international program conserves habitat, restores forests and fisheries and builds sustainable economies across 70 million acres in the world’s largest temperate rainforest, stretching from the Washington coast through British Columbia and into Southeast Alaska.

- International: Support from Washington allows Conservancy programs around the world to benefit nature and people, for example protecting elephant habitat in Africa through indigenous communities.

Forty-five donors gave gifts of $100,000 or more. The campaign was also supported by corporations and private foundations, including Boeing, Harriet Bullit’s Icicle Fund, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.

“What makes this campaign so special is our work with people—farmers, fishermen, loggers, business owners, tribal communities—to develop projects that will have the biggest impact on people’s lives and on our future,” said Mary Ruckelshaus, chair of the chapter’s board of trustees. “Using innovative, science-based solutions, we are making life better for people and communities while protecting the natural resources on which we all depend.”

Contact information

Robin Stanton

The Nature Conservancy

(206) 436-6274

rstanton@tnc.org