Get a closer look at the effectiveness of our log jams in Hurst Creek for restoring riverine habitat for Clearwater coho salmon.

From Trees to Seas: Marine Team Visit Ellsworth Creek

Written and photographed by Claire Dawson, Hershman Marine Policy Fellow

On our way to the Marine Resource Committee Summit in Long Beach, Washington, several members of the Marine Team here at The Nature Conservancy got the chance to visit forester, Dave Ryan, at Ellsworth Creek Nature Preserve. This 7,600 acre preserve encompasses an entire watershed, and links with the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. Together these provide more than 15,000 acres of refuge to species like nesting marbled murrelets, cougar, black bears, elk, amphibians, and salmon.

Our visit began with a tour of the recent log jams that have been installed upstream on Ellsworth Creek. These jams, while appearing to be no more than piles of brush and logs thrown haphazardly across a stream, are in fact an important natural feature of creeks and rivers. For decades, woody debris was removed from rivers and streams to promote navigation, recreation and beautify river beds. However, recent research has shown us that removing debris is detrimental to fish habitat. Recent creek restoration efforts have therefore focused on rebuilding these essential features.

By forcing the water over, under and around them, log jams slow the water and allow historical flood plains around creeks and rivers to fill and pool with water, providing a more favorable environment for returning adult salmon and growing fry. Slowing water flow also allows the deposit of larger sediment like rocks and rubble further upstream, creating the habitat needed for salmon to build redds and lay their eggs. These newly established woody areas also lower stream temperature by providing shaded environments, and somewhere to hide. Properly engineered, they also serve to reinforce creek beds, preventing erosion.

The Ellsworth Creek Preserve also encompasses an area of old growth Sitka spruce and Western red cedar. Following a one-mile trail down into the valley, we walked among giants, some over 800 years old to what’s known as Ellsworth Beach. With the recent rains and cooler weather, the group had hoped to see that the Chum had arrived in this part of the creek. Alas, the Chum prefer to arrive in solitude, and waited until the following day to show up in droves.

Our visit to Ellsworth served as a wonderful reminder of the interconnectedness of nature – and the various elements that work together to create habitat that is ‘just right’ for some of our region’s most beloved species. Conservation progress has implications far beyond the lands we walk on, and progress made on land has rippling effects all the way out to the deep blue sea.

Visit Ellsworth Creek Preserve

Fish of the Forest: Large Wood Benefits Salmon Recovery

Written by Emily Howe, Aquatic Ecologist

Photographed by Hannah Letinich, Volunteer Photgraphy Editor

Graphics by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

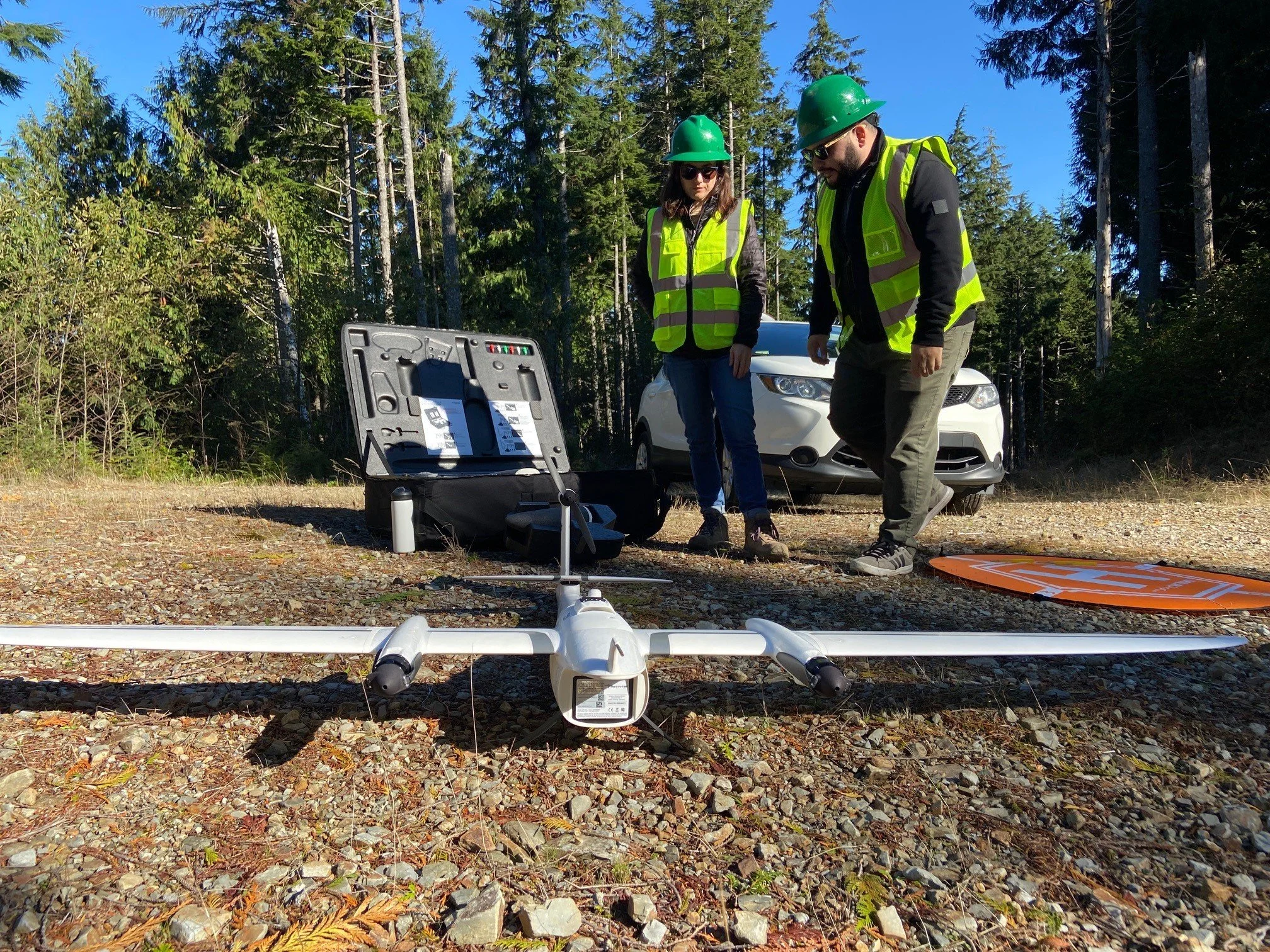

Boots. Any aquatic ecologist worth their salt needs a collection of boots. Rubber knee boots, lug-soled hiking boots, felt-soled stream boots, chest waders, and caulks. Caulks? Before last week, a sturdy pair of spike-soled logging boots had not made my inventory list as a fisheries biologist. Flippers, yes. Wet suit booties, sure. But generally speaking, spikes are left to those scaling glaciers or trees.

My recent trip to Washington’s coastal rainforests changed my footwear paradigm.

After a 3-day four-wheel drive tour of Ellsworth Creek, the Hoh, Quinault, and Clearwater Rivers, it is clear that active forest management goes hand in hand with salmon and river recovery. Rolling back a century of damage from industrial logging requires active logging operations to thin and replant monocultural tree plantations, decommissioning and rerouting roads, and reintroducing large wood into streams and rivers. The caulks come in handy on that last one.

You see, to enhance natural river processes critical to salmon and watershed recovery, The Conservancy and its partners are reintroducing fallen trees to streams and floodplains throughout coastal Washington, Puget Sound, and the Central Cascades. This restoration technique ranks as one of the most urgent actions needed for the recovery and future resilience of salmon because it promotes a complex portfolio of aquatic habitats. Once in the water, large wood initiates log jams that in turn increase natural scour, create new pools and deepen existing ones, provide slow-water refuge for juvenile fish, create gravel beds for nesting, trap nutrients in streams, and increase food availability.

The Conservancy’s coastal forest preserves embody the integration of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems- right down to the boots.

Introducing Emily Howe

Written by Tammy Kennon

Photographed by Hannah Letinich, Volunteer Photo Editor

Emily Howe remembers a time when there were so many salmon, “they would bump your ankles. You could pet them!”

Emily, the Washington Nature Conservancy’s newest staff member, saw those fin-to-fin salmon as a child while camping with her family at Lake Wenatchee on the east side of the Cascades. But over the years as her family returned to the same stream, she watched those salmon dwindle, a firsthand observation of how humans impact the environment that launched a career.

After completing a biology degree at Vermont’s Middlebury College, she continued her education at the University of Washington, Seattle, earning an M.S. and a Ph.D. in Aquatic and Fishery Science.

To add real life experience to her education, Emily studied abroad in the San Blas Islands, off the Caribbean coast of Panama, and in Tanzania, an opportunity to “further how we think about land and people.”

“You can’t leave the people out; you have to integrate them,” Emily says. “We’re trying to figure out how to transform our daily lives to include nature, to offer natural solutions. We don’t have to have a negative impact. It can positive.”

In her new role as Aquatic Ecologist, Emily has come full circle. She will focus on salmon recovery, measuring the success of Nature Conservancy land and freshwater restoration efforts.

“We’re trying to get back to a system that works and functions more naturally,” Emily says. “Sometimes that’s building something that works like nature does.”

The Nature Conservancy efforts include rebuilding logjams to restore ecological processes in streams and bringing clear cut slopes back to their critical and natural place in the ecosystem.

Emily lives in Seattle with her husband and two children, 2 and 5 years old. They go camping, hiking, biking, clam digging, and other outdoor pursuits, “trying to get as dirty as we can.”